From the hard-partying era of the late ’70s and early ’80s, a time when a crime of passion could be excused—culturally and legally—comes a tragic tale of sex and violence among the wealthy class in Brazil. In the February 1983 issue of Cosmo, we explored the torrid story of socialite Angela Diniz and her playboy/hustler boyfriend Doca Street, and how their affair forever changed a nation. —Alex Belth, Hearst historian

She was known as the Panther of Buzios, a sleek Brazilian beauty who liked to boast, “I’m rich, beautiful, and good in a fight.” He was a Rio playboy, without money or job, who’d used his considerable charm to marry—and later abandon—three Brazilian heiresses. Together, sharing her beach-front villa in Buzios—three hours from Rio and one of the most sought-after anchorages on the 500-mile Brazilian Riviera—this celebrated couple carried on a tempestuous affair. But after three months, Angela Diniz, thirty-two, finally grew tired of financing the expensive tastes of her forty-five-year-old Latin lover, Raul Doca Street, having lavished Italian suits on him as well as French cognac, American cigarettes, and, reportedly, Bolivian cocaine. At the end of one long hot day of vodka, backgammon, and quarrels over the favors of a mysterious German girl, Angela told him to move out and make room for a replacement. He refused. She insisted. And so they quarreled bitterly. It was a fight that would end in tragedy.

Ever since her debut at the age of fifteen, Angela Diniz—with her lustrous jet-black hair, almond eyes, high cheekbones, and sensuous mouth—was one of the most beautiful (and envied) women in all Brazil. A manicurist in Copacabana polished her nails, smoothed her sleek long legs, and waxed away any stray hair so that Angela could wear the tiniest of string bikinis—usually with a panther stamped on the crotch. (In Brazil, a gorgeous girl is called a gatinha, meaning kitten, but so successful was Angela at using her seductive good looks to stalk men and set their hearts afire that Rio’s society columnists elevated her to the rank of pantera.) Often figuring high on the list of best-dressed women, she favored black velour, gold earrings, designer fashions from Paris, New York and Rome.

At seventeen, Diniz married Milton Vilas Boas, a wealthy engineer from a traditional family in Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s third largest city and a stronghold of social conservatism. After five years and three children, the marriage failed. To Angela’s everlasting despair, the judge awarded custody to her husband. Yet between the divorce settlement and an inheritance from the Diniz clan, she was free of financial worries. She owned a downtown office complex, several building lots, and a mansion—all in the interior industrial city of Belo Horizonte.

Within no time at all, Angela embarked on a series of escapades that no only shocked the strait-laced town but earned her nationwide notoriety as “the most talked-about woman in Brazil.” And then one day in May 1973, this frequent item in the society columns began making headlines in the news. The crossover came when her lover at the time, Artur Vale Tuca Mendes, a member of the local aristocracy, unexpectedly returned home to find Angela in bed with a man hired to guard the house. Tuca shot the guard dead, but instead of immediately notifying the police, he called on friends to help him drag the corpse outside and wrap a kitchen knife in the stiffening fingers of one hand.

Angela arrived at the sensationalized pretrial hearing shielded by sunglasses and decked out in a rose-colored designer dress. Sweeping through a forest of clicking cameras and exploding flash bulbs, she announced to the press that the guard had tried to rape her. In court, detectives said they found the guard’s pubic hairs on her sheets—and also pieces of Diniz’s clothing (underwear and an imported French shirt) in the guard’s room. The jury couldn’t determine what really had happened, and so both Angela and Tuca were acquitted of any wrongdoing. “Those who knew Angela intimately would know she’d never give intimacy to a servant,” sniffed Ibrahim Sued, Rio’s most influential society columnist, who’d often intimated that he, too, had been caught in the Panther’s claws.

Her affair with Tuca at an end, the Panther took to prowling sophisticated seaside Rio. There, she owned an apartment on quiet, tree-lined Anita Garibaldi Street—a five-minute walk from Rio’s crescent-shaped Copacabana Beach, a stretch of sand a songwriter once described as “the little princess of the sea.” It was in this flat, among the tropical plants, wicker furniture, and sisal carpets, that police, in September of 1975, discovered several packets of marijuana cigarettes. Jailed for twenty-four hours, Angela was released only after declaring a drug dependency. “Everyone smokes grass—but me, I have to get caught,” the socialite groused to Sued. A few months later, she brought her younger daughter to Rio for a weekend, violating the child-custody agreement. Arrested for a second time, Diniz was convicted of kidnapping. Whereupon, having been given a suspended sentence and convinced she would never win back her son and two daughters, the Panther attempted suicide in her Rio apartment—only to fail at the effort.

At this low point in her roller-coaster life—in late September of 1976, to be precise—Angela met Doca. She hoped this tall, aristocratic man would bring her peace and privacy. But within three months, his only gift would be lasting notoriety.

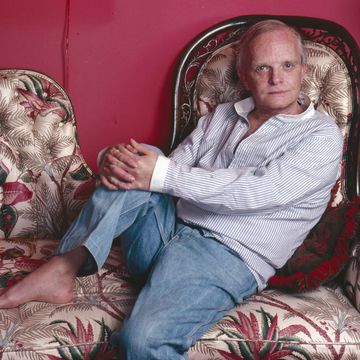

In a nation of handsome men, Raul Doca Street stood out as a full-time successful playboy. With no money of his own, he was continually supported by one or another of Brazil’s most beautiful—and richest—women. Blessed with striking good looks and a well-worked athletic body built on a tall frame, Doca skillfully mastered a commanding gaze. Once having caught a woman’s attention, he would break into a languorous, self-confident smirk, dimpling a tanned cheek and flashing a perfect string of pearl-white teeth. An impeccable dresser, Doca cut a fine figure in white shirts, European-cut navy-blue suits, and gleaming black loafers. In night clubs or at intimate dinner parties, he sported silk shirts open to the navel, revealing a mass of silver-flecked chest hair.

Woman after woman melted before him. Doca, in turn, readily recognized his power over the female sex and lost no time capitalizing on it. In the early ’60s, he and a friend had set out for Miami, reportedly with only two dollars in their pockets. Doca claims he survived initially by serving as a swimming instructor, but Brazilian press reports say he thrived by “entertaining” wealthy women in Miami Beach. In any event, he stayed in the U.S. for two years, learning fluent English and, by his account, working in Washington as secretary to an African ambassador and subsequently as a doorman at the exclusive Sans Souci restaurant, just one block from the White House.

On returning to his native Sao Paulo, Doca married the wealthy Stella Arens and invested in several stock-market and real-estate ventures—all of which fell through. In 1973, he met, Adelita Scarpa, daughter of a powerful Sao Paulo industrialist. Quick to divorce his first wife, he went to live with Adelita in her luxurious mansion in the exclusive neighborhood of Paulista Gardens. Eventually, they married and had a child.

During this period, Doca was fond of bragging that he lived with his new wife as an Indian nabob, lavishly entertaining friends with the best wines and regularly frequenting Sio Paulo’s most popular night clubs. “When people asked him about his work,” said one friend, Kiki Garavaglia, “he’d answer, ‘Work? Me? Never again.’” Indeed, his income-tax statements show that for the three years of his marriage, he earned twenty-five dollars a week from companies owned by his brother-in-law. “The nasty little secret about Doca,” said another friend, “is that he never had a cent.”

Only weeks after meeting Angela, Doca deserted his second wife, their child, and a secure financial future—all for a gamble with the Panther. The breakup with Adelita was not pretty. When Doca started stuffing his clothes into suitcases, Adelita said they were her bags. So he threw his clothes into two sheets. They were her sheets. Finally, he stomped out of the Sao Paulo mansion carrying his clothes in his arms. “Angela drove me wild,” Doca would later confess. “I abandoned the wife and child who loved me.”

“They were so intense,” Kiki Garavaglia recalled of Doca’s first days with Diniz. “Theirs was the kind of passion only seen in novels.” To be sure, the headstrong Panther had turned affectionate kitten, going to all lengths to satisfy her lover. Despite Brazil’s 200-percent tax on luxury imports, Angela generously filled Doca’s liquor cabinet with Russian vodka and French wines. She bought him Marlboro cigarettes by the carton. And she replenished his wardrobe with custom-made suits, slacks, shirts, sports coats, and silk ties—all from the finest tailors abroad. Their life together was one prolonged honeymoon, which they eventually decided to spend in permanent residence at Buzios.

Lying 100 miles north of Rio, Buzios is the preferred seaside escape of the rich and powerful. It nestles at the top of what is emerging as the Brazilian Riviera, which runs down the Atlantic Coast to Sao Paulo, harboring a strand of exclusive marinas, condominiums, private islands, golf courses, tennis courts, and beach-front villas. Here, lounging in low-slung dune buggies and sports cars, bare-chested men slowly cruise the village’s sandy streets, while bronzed women in string bikinis window-shop the fashionable boutiques.

It was in late November, two months into her affair with Doca, that Angela made the down payment on a $50,000 Buzios beach house, one of a row of sixteen fronting on a much-coveted fingernail of white sand called Praia dos Ossos. In line with the exclusive community’s carefully maintained image of casual chic, the Panther’s one-story villa was built in neofisherman style—whitewashed stucco, green shutters, orange tile roof, with track lighting inside. A luxuriant tropical garden filled the rear, and a coral-pink hibiscus bloomed in front. Two massive trees—one a flamboyant and the other an ancient fig—provided shade against the strong equatorial sun. Thirty feet from the bedroom window was the beach. At night, a cooling breeze blowing in from the South Atlantic, Angela and Doca could listen to wavelets lapping on the fine white sand.

“All the time they were here, all they did was go to the beach, eat, and go to bed,” remembered Manoel Aurelio de Souza, a retired fisherman whom Angela had hired at $150 a month to work as houseman. Completing the household staff was Souza’s daughter, Ivanira, who served as a live-in maid; Maria Jose de Oliveira, the personal maid Angela had brought with her from Rio; and Marizete Quin tan i! ha Porto as cook. “Each day, they would invent a new dish for Marizete to do,” said Manoel.

As Christmas approached, Angela and Doca traveled to Belo Horizonte to spend the holiday with her family, who, to the Panther’s disappointment, were not at all impressed by her new man. Actually, the relationship that started off like a rocket had already begun to fizzle, with Doca growing increasingly jealous and Angela longing more and more for lost freedoms. “She lived under permanent oppression by him,” recalled Francisco Matarazzo III, a Sao Paulo millionaire, who had lunched with the couple in their Rio apartment on their way back from Belo Horizonte. Doca, who was initially attracted by Angela’s provocative charms, now demanded that she adopt a more conservative style. “He wouldn’t let her wear this dress or that blouse—he wanted to be in charge of everything,” said Matarazzo.

Others close to Angela used the word “clinging” to describe Doca’s new attitude toward Angela. By the end of December, one woman remembered, Angela could telephone friends only when Doca was in the shower. When he turned off the water, she’d hang up. Not to be declawed, the Panther finally confided to a girlfriend, “I’m starting 1977 without Doca!”

Angela’s personal maid, Maria Jose, was the closest eyewitness to the finale of a deteriorating affair that only three months earlier had been a morass of passion. “The day before we went back to Buzios, Dona Angela asked for her blue dress,” recalled Maria Jose. “He didn’t like it. She asked for her yellow outfit. He didn’t like it. Then she locked the bedroom door, but it just got worse. He started beating and kicking, trying to force it. Finally, he threw his whole weight against it. Then he threw himself on her, kicking and punching her. I ran in to help, and took a whack. A real scandal. The truth is that he was a vagabundo who never worked and lived off her back. He wanted a joint account and all the property in his name.”

According to this maid, Doca’s violent nature erupted again the following day, a Wednesday. They had arrived at the Buzios beach house, only to find five plasterers and stonemasons still at work on renovations that were to have been completed during the couple’s absence. Doca tried to kick one of the laborers, missed, kicked a table, and injured his foot. Later that evening, hoping to relax, he and Angela went out for drinks at the Hibiscus Pension, a nearby bar owned by a French friend. But instead of lifting the tension, that evening over drinks brought them a harbinger of doom in the person of Gabrielle Dyer, a German beauty who would unwittingly play the starring role in a fatal triangle.

Gabrielle was in Buzios peddling handcrafted backgammon sets—the game then the rage of cafe society. Usually attired in nothing but a skimpy, overworked bikini, she easily fit in as part of the wealthy international driftwood that populates the seaside resort. Gabrielle, it turned out, was a native of East Germany who’d grown up in the West, married a Canadian, eventually divorced, returned to Europe, and then moved on to Australia, where she ran a highly profitable escort agency designed to help businessmen meet young women. After two years, she wandered again, first the Pacific (the Fiji Islands, Honolulu) then to Mexico City, Acapulco, Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires, and, finally, Rio, breezing into town just in time for the February carnival celebrations—five wild nights of dusk-to-dawn street dancing and costume balls.

In Rio, Gabrielle had rented an apartment on Ipanema Beach. The tropical sun tanned her body a golden brown, sprinkled freckles across her high cheekbones, and bleached her boyish hair a flaxen blond. When November came, she followed the migration of the rich and beautiful to the selective beaches of Buzios.

Angela, intrigued by the German girl, offered to buy one of her backgammon sets. But after paying for several hours’ worth of chilled Russian vodka and caviar canapes, Diniz didn’t have enough money in her purse for the set. So she made a date to meet Gabrielle on the beach the following day, at which time Angela would pay the thirty-three dollars and Gabrielle would teach her how to play.

Slightly hung over from the night before, Angela awoke the next morning to the hammering of stonemasons installing a television antenna. Doca remembered the noise beginning early—around nine-thirty or ten o’clock—but the couple stayed in their large wicker bed until noon. At twelve-thirty, they walked out their front door and down the twenty steps to the beach. Seeing friends, Angela called to the maid for glasses, an ice bucket, and a bottle of Russian vodka.

Friends continued to come and go all day, and toward the end of the afternoon, Gabrielle stopped by to collect her money for the backgammon set and to instruct Angela and Doca in the game. Angela had already had four vodkas, but when she saw the bikini-clad German girl, she called up to the house for another bottle and, according to Doca, “asked Gabrielle to sit near her on the same towel. Angela wanted to photograph Gabrielle and me together and embarrassed us by insisting that I put my arm around Gabrielle.” Then, when he tried to take a picture with the Polaroid, he ruined the film—to the amusement of Angela. Irritated by her public ridicule, Doca walked back to the house.

“After Doca spoiled the film,” Gabrielle would later recall, “Angela took advantage of his absence to start making passes at me. I’d already noticed her different looks at me, but then she started passing her hand over my body in a strange way. I felt very self-conscious and didn’t know what to do.”

When Doca eventually returned, Angela, dressed only in string-bikini bottom and a translucent halter top, suddenly ran into the waves. “I ran after her,” said Doca. “We played a bit, then she said that she liked the German girl a lot. She said, ‘I’m going to take her home—and let’s have a threesome.’ I said, ‘You know I love you a lot. This hurts me. Don’t do it. Stop drinking.’ Then she went swaying out of the water and fell on the German girl.”

“She came out of the water and fell on top of my body,”remembered Gabrielle. “Doca quickly came to help her up. When he was lifting her, she gave him a kiss, but on kissing him, she caressed my leg. I didn’t like it, and I left.”

Sulky at Gabrielle’s rejection and Doca’s interference, Angela left the beach, returned to the house, and threw herself on her bed. She slept for two hours. On waking, she asked the cook to prepare some scrambled eggs.

Hearing that Angela was up, Doca went into the bedroom and sharply criticized her conduct. Tempers flared, and a shouting match ensued. “You’re no good. Go away. You’re no good,” neighbor Celia Carvalho da Silva recalled hearing Angela shout at Doca. “I don’t deserve what you did to me,” Marizete, the cook, remembered Doca telling Angela. “I don’t deserve it. There’s no excuse for what you did.” When the a voices continued to rise and the language became even harsher, Marizete and the other two servants discreetly slipped out of the house, as they had done on other occasions.

This time, however, the fighting did not stop. According toDoca, Angela screamed at him, “Go away. I can’t stand you any more, I can’t do what I want any more. You’re very possessive. Pack your bags . . . and get out!”

His Latin sense of machismo inflamed, Doca threw some clothes together and, stalking out before the startled servants, hurled his bags in Diniz’s car. Then, controlling himself for a moment, he went back inside. In his words, “She was in the bathroom. At the time, I thought there would be a reconciliation. She was combing her hair. I tried to kiss her, but she pushed me away. She left the bathroom and went to sit outside on the veranda.

“I knelt before her and asked her to forgive me because I loved her deeply and wanted to be happy with her, to start a family and realize all my dreams. She agreed, but then she made demands. ‘You have tied me down too much. You are going to have to share my love with men and women. You will see how good it will be ... ’

“I couldn’t stand it... Angela took my shoulder bag, which was on the bench, and threw it in my face. The bag opened and my Baretta fell out.” Doca picked up the semiautomatic. Standing less than five feet from his beloved, he fired once into her forehead. The pistol jammed. He paused, unjammed the gun, fired twice into her upraised right arm and three more times into her head, hitting the right eyebrow, the right cheek, and the right temple. A seventh bullet dug into the stucco wall.

Doca left Angela prostrate, her blood splashing over an ornamental urn and whitewashed love seat and collecting in a dark pool on the glazed patio tiles.

“Suddenly, from outside, we heard the shots,” recalled Manoel, the houseman. “Then we saw him run, dressed only in a bathing suit, carrying a little bag.”

Leaping into Angela’s coffee-colored Maverick, Doca took off and sped fifteen miles down a dirt road to Cabo Frio, the nearest town. There, he said, he stopped in front of the police station to turn himself in: “I was only dressed in shorts, and I decided to put on a shirt and pants. Then I remembered my child, my brother, my father, my mother—and I decided to say goodbye to them.” Straight through the night, Doca drove 375 miles to the south, arriving at 4:00 a m. in Sao Paulo, where he promptly vanished from sight.

Three weeks later—in late January—he was arrested in a private clinic for alcoholics and drug addicts. Flown that night to Rio, the once trim and elegant Doca was photographed in an alcoholic stupor—disheveled clothes, a three-day growth of beard, eyes half-closed, chin sunk down on his chest—supported by two burly policemen. He would spend the next six a months in jail.

While Doca was behind bars, the sensation of the case became Gabrielle Dyer, who remained a familiar figure on the beaches of Buzios, charming the hordes of reporters with her habit of sunbathing topless. She gave interviews attired only in a string bikini and held a nationally televised press conference dressed in Indian sandals and a white print sundress that concealed almost nothing.

Gabrielle’s testimony was crucial in supporting Doca’s version of the murder, but just when he was released on bail, the German girl disappeared. She was last seen in May 1977 in the company of an Argentine friend, Mercedes Avellaneda, twenty-one. As Mercedes told the story, she and Gabrielle had decided to lunch at Horseshoe Beach, a spit of sand accessible only by a perilous cliffside trail—a path the athletic German girl knew by heart after eight months of exploring the area. As the pair clambered up a steep rock near the summit, Gabrielle’s handhold suddenly slipped and she fell backward in a long curving arc. For a few minutes, Mercedes could see her friend floating in the surf. And then the current carried the body out to the open sea.

After notifying police of the accident, Mercedes left for Buenos Aires, never to return to Buzios. A short time later, her brother, Marcos, was indicted for selling drugs in Buzios; he, too, permanently left Brazil. And an inspection of Gabrielle’s German passport showed that two days before her disappearance, she’d entered Brazil from Santa Cruz de la Sierra—a dusty Bolivian border town notorious as the major embarkation point for Brazilian-bound cocaine. Coincidence, perhaps, but it led to speculation that she may have started catering to a new taste among the Buzios jet set more expensive than backgammon: Bolivian cocaine.

Whatever Gabrielle’s fate, Doca was set to face his in October 1979, when, nearly two years after he shot Angela, the murder came to trial. Admirers packed the small Cabo Frio courtroom, and 500 onlookers, many of them women, gathered outside to wave banners bearing legends like DOCA, CABO FRIO IS WITH YOU and CABO FRIO HAILS DOCA STREET. Carried away by the glamour involved, the Brazilian media blanketed the case. Television channels broke into regular programming to bring bulletins live from the scene. One network sent twelve reporters and fifty-six technicians. The tall, handsome Doca became a star—a symbol of beleaguered, abused machismo.

Amazingly, both of Doca’s former wives sent letters of character reference to bolster his defense, and he was able to marshal fifty additional letters from prominent bankers, lawyers, and businessmen—including the former president of the Jockey Club and the owner of Sao Paulo’s dominant newspaper.

As counsel, Doca hired Evandro Lins e Silva, a former Supreme Court justice. Calling Angela “a scarlet woman of the kind we have been warned about in the Apocalypse,” he argued that she’d “committed suicide using Doca as the instrument. He knelt down,” boomed Lins, “asked for her forgiveness, and when he felt she was going to pardon him, he was insulted in his male dignity. She said, ‘Look, cuckold, if you want to live with me, you’re going to have to allow me to make love with other men—and women.’” The court audience responded with a standing ovation as Lins wept.

By a vote of five to two, the jury convicted Doca of the mild charge of involuntary manslaughter, and he was given a two- year suspended sentence. The Latin lover walked out of court a free man. MACHISMO IS ABSOLVED, trumpeted newspaper headlines. “I thought it was great,” gushed Tania Regina Anabai, a student. “He’s a real loaf of bread [Brazilian slang for ‘good looker’]. He shouldn’t be in jail.” But another bystander, Helio Maranhao, sounded a prophetic note: “He should have gotten the maximum sentence. Now a lot of guys are going to go out killing women.”

Not surprisingly, shocked by the leniency of the court and by a premonition that crimes of passion would spread, Brazilian feminists pressured for a new trial. Bare walls in Rio began to be spray-painted with such legends as if IF DOCA IS NOT PUNISHED, OTHERS WILL DIE OF LOVE, TOO and END THE HUNTING SEAONS ON WOMEN. “We made more noise than our small numbers would suggest,” according to Rosemarie Muraro, head of the Brazil Women’s Center in Rio, who estimates there are only 10,000 militant feminists among Brazil’s 60 million women. But, in her words, “We have no small impact on public opinion.”

Buoyed by growing popular support, Angela’s family appealed the 1979 jury decision. A higher court overturned the verdict, annulling it on the grounds that it was “manifestly contrary to the proof contained in legal records.” Raul Doca Street would have to stand trial again.

A year ago last November, the morning of the retrial dawned sunny, and up to 2,000 spectators packed the courthouse square. Food vendors, arriving early, did a booming business in popcorn, peanuts, hot dogs, sandwiches, meat pies, corn cakes, fried shrimp, sticky candies, and freshly squeezed sugar-cane juice.

As Brazil’s national symbol of machismo, Doca could no longer leisurely saunter up the courthouse steps bestowing his leering grin on female cheerleaders. Instead, twenty military police had to escort him through a mob of 500 angry feminists, who greeted the aristocratic playboy with shouts of “Jail the gigolo!” and banners bearing the slogan QUEM AMA. NAO MATA—LOVERS DON’T KILL. Inside, the judge’s opening words were drowned out by a television reporter interviewing Milton Vilas Boas Diniz, eighteen, Angela’s son. “Contrary to what that guy [Doca] goes spreading around, she was a very good woman for all the family,” said young Diniz. “I wish I could kill him with my stare.” He then went on to gaze steadily at Doca for most of the eighteen-hour trial.

For his part, Doca adopted a contrite, downcast pose, ignoring hoarsely whispered entreaties from photographers to “look over here.” He repeatedly used a white handkerchief to mop away perspiration caused by the heat of the television lights. At one point, the black-robed judge stopped the proceedings to place Doca where he wouldn’t melt away but could still afford the photographers a satisfactory angle.

Despite a reported $21,000 fee, Doca’s new defense lawyer, Humberto Teles, did not match the Biblical oratory of his predecessor from the Supreme Court. Teles described Angela as a “woman who traded her three children for Rio’s night life,” while Doca was merely a big boy with a gypsy soul, a model citizen who lived quietly with his mother in Sao Paulo.

There was little suspense as to the outcome. By a decision of five to two, Doca was convicted of murder and sentenced to fifteen years in prison—a decision reported by one newspaper even before the trial started. Citing that article, the defense appealed the case. The higher court, however, denied the appeal, and on October 6, 1982, Doca went to jail. He is now lodged in Cell 21 in Gallery 6 of Civilian I at Rio’s Lemos de Brito Penitentiary.

When last heard from publicly on the matter, Doca’s lawyer, Humberto Teles, had harsh words for the feminist demonstrators, who, he charged, had “manipulated public opinion” against his client. “They are Hitler’s daughters,” he said after the trial, “fascist women with a clear homosexual component. Juries understand that a man can kill a woman when his masculinity is offended.”

That was certainly true in the past, but many observers believe that Doca’s defeat has finally signaled an end to the legitimization of crimes of passion in Brazilian courtrooms. In the two weeks following the verdict, juries in Angela’s conservative home state of Minas Gerais deliberated at three separate trials having to do with men who killed their wives out of “legitimate defense of honor.” In each case, the defendant was found guilty of murder.